Truth is Power • Science Enables Creation • Knowledge is Difficult • Discovery is Possible • Learning Requires Progress

If you had to point to the most impactful philosophical insight since antiquity, what would it be? There’s a good case to be made for scientific induction.

While science itself is at least as old as fire, the incredible progress of the last few centuries would not have been possible without a good scientific method – or at least one better than accidental discovery.

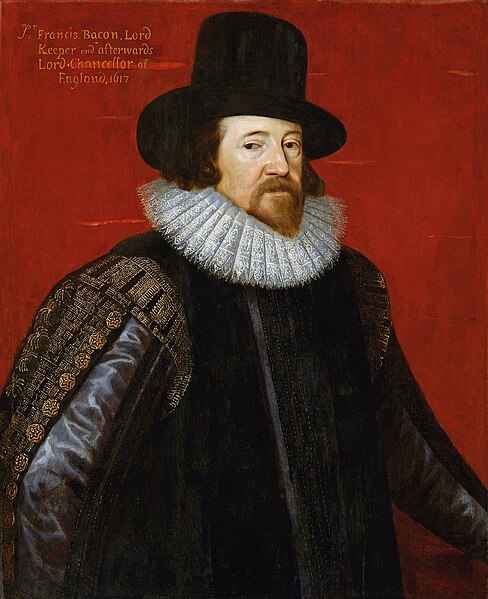

Before Newton, Noether, Einstein or Curie, there was Bacon.

🥓🐷

The 1st Viscount St. Alban, Francis Bacon, was born in London in 1561. In 1618, he was appointed Lord Chancellor, the highest minister of the crown. Three years later, he was charged with corruption, stripped of his position and briefly sent to the Tower of London. And in between, he published Novum Organum – “True Directions Concerning the Interpretation of Nature”.

Bacon’s treatise on “natural philosophy” begins with an indictment of classical interpretations of natural law. In broad brushstrokes, Bacon paints an ambitious program for developing a new scientific method.

🎨🖌

Bacon’s treatise draws its name from Aristotle’s Organon, which lays out the methods of deductive logic and syllogism. Bacon saw these as insufficient tools for the development of science, often improperly applied to unproven premises. Aristotle responded to this criticism by dying nineteen centuries earlier.

The treatise contains two books: the first on criticisms of prior methods, and the second on steps towards an improved induction. These books are divided into aphorisms. References below will indicate the book and aphorism number in the form [B1A1].

📚📖

The Novum Organum doesn’t actually deliver new scientific laws, or even a fully-functional method (though this is attempted in the second book).

What it does well is provide a brief history of protoscience (how people did science before the method), in which Bacon highlights a number of biases, assumptions and errors people tend to make.

Bacon’s insights are as much about humanity as they are about nature – probably more. While not a particularly notable scientist, he is certainly a notable philosopher of science.

Where else … does one come across a stripped-down natural-historical programme of such enormous scope and scrupulous precision, and designed to serve as the basis for a complete reconstruction of human knowledge which would generate new, vastly productive sciences through a form of eliminative induction supported by various other procedures including deduction?

Rees & Wakely, 2004, The Instauratio Magna, Part II: Novum organum and Associated Texts

1. Truth is Power

Wills to Power 👑

Bacon says people want power for three reasons [B1A129]:

- They want more power in their country

- They want their country to have more power

- They want humanity to have more power

Unsurprisingly, the Most Important Politician in England™ thought that other people trying to have more domestic power was “vulgar and degenerate”.

On the other hand, Bacon thought that imperial expansion had “more dignity, though not less covetousness”.

However, the last goal – humanity’s power over nature – is “without doubt both a more wholesome and a more noble thing than the other two”.

💣⚔️

Bacon wants to make it clear that the pursuit of science shouldn’t be political. One person’s power over nature benefits others, so long as that power is shared. Science is a humanist pursuit.

In fact, this isn’t limited to natural sciences. The “empire of man … depends wholly on the arts and sciences” [B1A129]. Science and the humanities are complementary magisteria, to be developed alongside one another by individuals and society.

Truth is a Means of Power 💪

Power over the universe sounds great, but how do we get it? Bacon says we need to know more about the causes of things.

If a man be acquainted with the cause of any nature (as whiteness or heat) in certain subjects only, his knowledge is imperfect; and if he be able to superinduce an effect on certain substances only (of those susceptible of such effect), his power is in like manner imperfect.

B1A3, Novum Organum

You can only effect change to the extent that you understand the cause. “Nature, to be commanded, must be obeyed; and that which in contemplation is as the cause is in operation as the rule” [B1A3].

Principled action requires a good model of interaction.

⚙️🌦

To invent and innovate, we need abstractions and inductions. Abstractions are general rules or concepts we get by observing the world. Induction is how we generate useful, correct abstractions.

We wouldn’t have split the atom without nuclear physics. No sane person would travel to the moon without classical mechanics.

Truth is a Tool 🔧

Bacon didn’t foresee the extent to which science was misused in the twentieth century. But he did emphasise that science is a tool, not a panacea.

Science and the humanities may be put to “purposes of wickedness, luxury, and the like”, but “the same may be said of all earthly goods: of wit, courage, strength, beauty, wealth, light itself, and the rest” [B1A129]. Throughout the first Book, he argues that the benefits of scientific and technological progress justify their difficulty and misuse.

Start with the Basics 👶

Science may be a tool, but that doesn’t mean we should use it expediently. Bacon presents two cases in defence of pure science:

- Creation is divine in origin, and must be understood in itself, not with man as its measure

- Basic research is necessary to uncover and justify the broadest, abstract principles of applied sciences

At first, and for a time, I am seeking for experiments of light, not for experiments of fruit, following therein, as I have often said, the example of the divine creation which on the first day produced light only, and assigned to it alone one entire day, nor mixed up with it on that day any material work.

B1A121, Novum Organum

The first argument can be taken either as an argument from religion, or as an argument from aesthetics.

This is a pretty standard defence of pure scientific discovery. Pure science is to applied science what theurgy is to thaumaturgy.

Bacon goes so far as to argue that “works themselves are of greater value as pledges of truth than as contributing to the comforts of life” [B1A124].

🏔⛪️

The second argument is more powerful, since it argues from the perspective of someone who already values applied science.

Pure science reveals general rules for how the universe works. These apply to a whole range of fields at once. Drawing these connections lets applied scientists think more effectively, “to detect and bring to light things … which would never have occurred to the thought of man”, and to have “truth in speculation and freedom in operation” [B1A3].

🛠💡

The pure/applied distinction is manmade. Effective scientists need both sides. Without a “pure” understanding, we can only stumble towards (or away from) a solution – we “may arrive at new discoveries” but will “not touch the deeper boundaries of things” [B1A3]. Without an “applied” mindset, there is no problem to solve.

Experiments are great, but you can’t make good hypotheses without a good model. Applied science without any pure science becomes pseudoscience.

Prove the Obvious ☀️

There are many things in this History which … will seem to be curiously and unprofitably subtle.

B1A121, Novum Organum

To do science well, you need to explain both the common and the uncommon.

Obviously planting seeds can produce vegetation. But why?

Obviously lighting a fire can produce heat. But why?

He who will not attend to things like these as being too paltry and minute, can neither win the kingdom of nature nor govern it.

B1A121, Novum Organum

“Obvious” often means “fundamental” – everything else depends on these. As Bacon puts it, “the letters of the alphabet in themselves and apart have no use or meaning, yet they are the subject matter for the composition and apparatus of all discourse” [B1A121].

🌱🔥

Questioning and justifying facts and beliefs that seem obvious has two main purposes.

The first purpose is to get rid of beliefs which seem obvious, but are actually false – these are quite dangerous, because we are less likely to question them. A good reason to discard the obvious is probably a fundamental insight.

It may be “obvious” that the universe has no speed limit, since an object can always travel faster than its current speed if given more energy. But it’s also false. If you knew why, you’d have a good head-start on special relativity.

The knowledge of simple natures well examined and defined is as light: it gives entrance to all the secrets of nature’s workshop, and virtually includes and draws after it whole bands and troops of works, and opens to us the sources of the noblest axioms; and yet in itself it is of no great use.

B1A121, Novum Organum

The second purpose is to gain a deeper understanding of your own thought process. If you know why you believe those “obvious” things, you can build a more conscious map of your assumptions and inferences. Confidence in our conclusions requires confidence in our premises.

This can help explain why something isn’t working as you expect it to, or what you might expect in different circumstances. It also lets you see where the weak points in your understanding are, or even to spot biases in your thinking.

🧠🕯

Examining the obvious lets us challenge it, and can be a valuable form of introspection. However, we should also be sure to accept it when it is reasonably proven – what can we know if we don’t know the obvious?

Questioning the possibility of knowledge or the importance of observation doesn’t help us turn observation into knowledge.

It doesn’t make sense to question whether truth is meaningful, since saying “truth is meaningless” is the same as saying “‘truth is meaningless’ is true”.

Contradictory observations doesn’t invalidate observation – it’s our responsibility to find a sensible interpretation that eliminates the contradiction.

All subtlety of disputation and discourse, if not applied till after axioms are discovered, is out of season and preposterous, and that the true and proper or at any rate the chief time for subtlety is in weighing experience and in founding axioms thereon. For that other subtlety, though it grasps and snatches at nature, yet can never take hold of her.

B1A121, Novum Organum

2. Science Enables Creation

Science isn’t just about describing. General principles help us generate new ideas – we need science to invent, innovate and improve our technology.

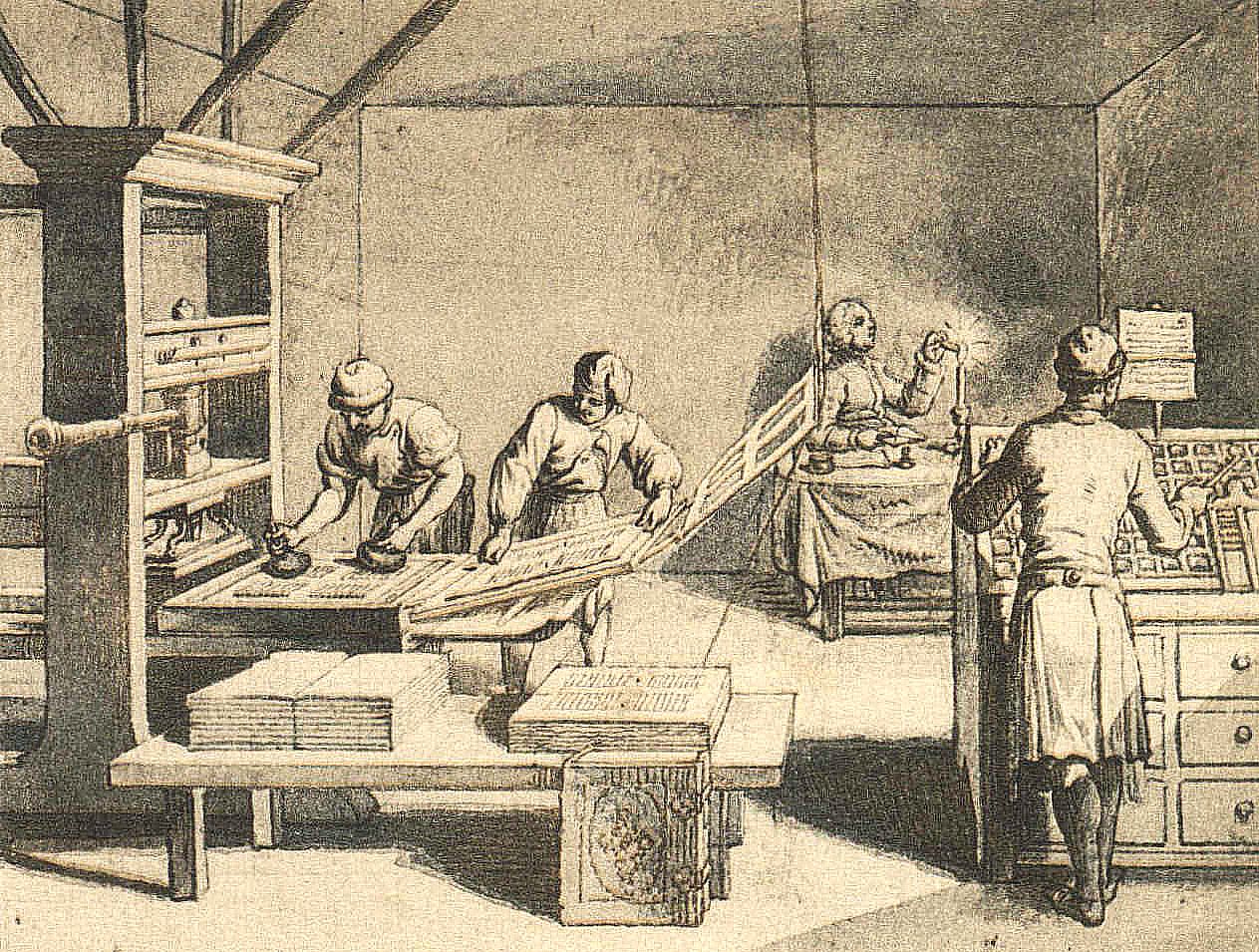

Printing, gunpowder, and the magnet … these three have changed the whole face and state of things throughout the world; the first in literature, the second in warfare, the third in navigation … no empire, no sect, no star seems to have exerted greater power and influence in human affairs than these mechanical discoveries.

B1A129, Novum Organum

Good philosophy lets us organise and synthesise knowledge and discoveries. Bacon’s book isn’t about how to observe nature, but how to interpret it – hence the subtitle, True Directions Concerning the Interpretation of Nature.

If we want to be creative problem-solvers, we need to organise the facts.

It’s not enough to define the problem – we have to define it well, and science lets us figure out the most elegant description. Knowing the definition of even numbers and primes and is not enough to prove that every even number can be written as a sum of two primes, even though this is a purely analytic claim.

Having all the data used in a solution isn’t enough to produce it. There is “nothing in the art of printing which is not plain and obvious”, but it is still much newer than writing. Bacon worries that “noble inventions may be lying at our very feet, and yet mankind may step over without seeing them”. However, he is excited at the thought of “a great mass of inventions still remaining which not only by means of operations that are yet to be discovered, but also through the transferring, comparing, and applying of those already known … may be deduced and brought to light” [B1A110].

📊🖨

Knowledge should be organised based on how it is to be used, and what the simplest accurate description is. Failing to appreciate the effort involved here makes inventions seem either obvious or serendipitous in hindsight.

(By the way – this is another reason to prove or question the obvious, especially when it comes to fixed beliefs about what is not possible.)

If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.

Attributed to Henry Ford

We live inside the natural world. Knowing about this world lets us control it.

Creation and invention let us use it to get what we want. If we want to make humanity more powerful, we need invention and innovation.

The reformation of a state in civil matters is seldom brought in without violence and confusion; but discoveries carry blessings with them, and confer benefits without causing harm or sorrow to any.

B1A129, Novum Organum

Even if science can be misused, it is still necessary for curing illness, combatting climate change, and possibly even maintaining global peace.

🌡🧬

In fact, Bacon argues that invention and progress can help inspire discovery and prioritise truth. It’s hard to teach science well without a good answer to “when will we ever use this?”.

Bacon even thinks that “the secrets of nature reveal themselves more readily under the vexations of art than when they go their own way” [B1A98]. In other words, doing science for aesthetic reasons is sometimes worse than doing it for practical reasons, even if you care more about aesthetics.

3. Knowledge is Difficult

As men have misplaced the end and goal of the sciences, so again, even if they had placed it right, yet they have chosen a way to it which is altogether erroneous and impassable.

B1A82, Novum Organum

Caring about science isn’t enough – you have to be good at it, too.

According to Bacon, there are four kinds of reasons people often don’t think clearly or rationally – the idols of the mind.

Idols of the Tribe 🤷

All perceptions … are according to the measure of the individual and not according to the measure of the universe. And the human understanding is like a false mirror, which, receiving rays irregularly, distorts and discolours the nature of things by mingling its own nature with it.

B1A41, Novum Organum

Humans think everything is about them. We might assume, for example, that animals are incapable of tool use or planning.

Idols of the Tribe are part of human nature. The “tribe” in question is humanity.

If we want to deal with these, we need to figure out what they are, and then teach each other how to spot them.

Idols of the Cave 🔦

It was well observed by Heraclitus that men look for sciences in their own lesser worlds, and not in the greater or common world.

B1A42, Novum Organum

Individuals think everything is about them. We all have our own personal experiences and echo chambers. Fairly judging anecdotal evidence requires humility, especially when it carries emotional weight.

Idols of the Cave are unique psychological tendencies of individuals.

To overcome these, it helps to seek out diverse people and ideas. Your personal experience is probably not the average.

Find people who you disagree with and listen to them.

Compare your beliefs to the evidence, not (just) the other way around.

Idols of the Marketplace 💰

It is by discourse that men associate, and words are imposed according to the apprehension of the vulgar … ill and unfit choice of words wonderfully obstructs the understanding. Nor do the definitions or explanations … by any means set the matter right. But words plainly force and overrule the understanding, and throw all into confusion, and lead men away into numberless empty controversies and idle fancies.

B1A43, Novum Organum

Flawed discourse and reasoning can cloud our thinking.

Idols of the Marketplace tend to be problems of language or rhetoric. It often helps to define your terms, but bad definitions can be just as confusing.

Phrasing ideas clearly and impartially helps in understanding and applying them. It is important to appreciate the concepts we are invoking, and the assumptions we are making.

Idols of the Theatre 🎭

Lastly, there are Idols which have immigrated into men’s minds from the various dogmas of philosophies, and also from wrong laws of demonstration … all the received systems are but so many stage plays, representing worlds of their own creation after an unreal and scenic fashion … errors the most widely different have nevertheless causes for the most part alike … of entire systems, but also of many principles and axioms in science, which by tradition, credulity, and negligence have come to be received.

B1A44, Novum Organum

Cultures are based on shared dogmas and assumptions.

Idols of the Theatre can shape not only what we think, but how. Seeking out diverse thought can help us here, too.

However, questioning dogma often comes with a high social cost.

Cultural progress requires questioning assumptions. Free expression helps reason drive culture, not the other way around.

That which can be destroyed by the truth should be.

Kirien, Seeker’s Mask, by P.C. Hodgell

Protoscience 🔮

Bacon thinks previous attempts at science were insufficient. A good method should control and direct the mind away from idols and towards truth.

Nothing duly investigated, nothing verified, nothing counted, weighed, or measured, is to be found in natural history; and what in observation is loose and vague, is in information deceptive and treacherous.

B1A98, Novum Organum

Proper reasoning is hard. It’s amazing that we can even notice problems with our thinking, let alone correct for them, and Bacon actually suggests it is “some happy accident, rather than of any excellence of faculty … a birth of Time rather than a birth of Wit” [B1A78].

Before Bacon, there were brief ages of scientific invention and discovery, but these were far shorter than the dark ages that came in between. The wonder of a method is that it lets us replicate the success of the classical ages.

Naive Abstraction 🔅

People tend to find patterns where they shouldn’t, or generalise before they should.

We shouldn’t come up with rules until we’ve examined a diverse range of examples. People like to “leap or fly to universals [axioms] and principles of things” [B1A64].

By gradually building up from specifics to principles, we can approach a general theory – but we shouldn’t try to reach it immediately. Good science “derives axioms from the senses and particulars, rising by a gradual and unbroken ascent, so that it arrives at the most general axioms last of all” [B1A19].

The Empirical school of philosophy gives birth to dogmas more deformed and monstrous than the Sophistical or Rational school. For it has its foundations not in the light of common notions … but in the narrowness and darkness of a few experiments. To those … busied with these experiments … such a philosophy seems probable and all but certain; to all men else incredible and vain.

B1A64, Novum Organum

Naive Induction 🧮

Bacon also says it’s not enough to look at a large number of similar examples if we want to find rules for a diversity of situations. Conclusions drawn this way “are precarious and exposed to peril from a contradictory instance; and it generally decides on too small a number of facts, and on those only which are at hand” [B1A69].

We have to make sure the examples we look at aren’t subject to some kind of selection bias. We should also be careful not to overfit our explanation to the data available: if our theory seems overly complex, maybe it’s too specific.

It’s not that we can’t generalise at all, but we should make sure to use “proper rejections and exclusions; and then, after a sufficient number of negatives, come to a conclusion on the affirmative instances” [B1A69].

We need general principles to find patterns in nature. Bacon shows us the basics of how to generalise properly, but admits there is room for improvement. Science requires that we accept the validity of some kind of inductive reasoning, whatever the proper method is.

An astonishing thing it is to one who rightly considers the matter, that no mortal should have seriously applied himself to the opening and laying out of a road for the human understanding direct from the sense.

B1A82, Novum Organum

Even though science had problems before Bacon, he remained optimistic that changes in method might lead to changes in the effectiveness of science.

He was right, of course.

Neither historical stagnation nor the difficulty of the subject should make us doubt that progress is possible – but it will still require new tools, technologies or methods.

If during so long a course of years men had kept the true road for discovering and cultivating sciences, and had yet been unable to make further progress therein, bold doubtless and rash would be the opinion that further progress is possible. But if the road itself has been mistaken, and men’s labor spent on unfit objects, it follows that the difficulty has its rise not in things themselves, which are not in our power, but in the human understanding, and the use and application thereof, which admits of remedy and medicine.

B1A94, Novum Organum

Other People’s Work 🧐

Original discovery is hard work. Sometimes it’s easier to restate or combine things others have come up with.

When a man addresses himself to discover something, he first seeks out and sets before him all that has been said about it by others; then he begins to meditate for himself; and so by much agitation and working of the wit solicits and as it were evokes his own spirit to give him oracles; which method has no foundation at all, but rests only upon opinions and is carried about with them.

B1A82, Novum Organum

This can be helpful sometimes [B1A110], but we can’t have no original research happening. New ideas need to be created and considered. Eventually, the remixers run out of low-hanging fruit.

We need to take risks when we think, and question the originality of our ideas.

It is not enough to write an essay about a philosopher who died nearly four centuries ago. You need to add some possibly contentious opinions and interpretations. If you can’t possibly disagree with a claim, it can’t contain any new information.

Old discoveries pass for new if a man does but refine or embellish them, or unite several in one, or couple them better with their use, or make the work in greater or less volume than it was before, or the like. Thus, then, it is no wonder if inventions noble and worthy of mankind have not been brought to light, when men have been contented and delighted with such trifling and puerile tasks, and have even fancied that in them they have been endeavouring after, if not accomplishing, some great matter.

B1A88, Novum Organum

Relying on Consensus 👨👧👦

You probably shouldn’t expect progress on things which aren’t going to be questioned. Sometimes consensus isn’t justification enough for belief.

Even in scientific circles, groupthink and unchallenged assumptions persist – though often for good reason.

However, Bacon argues that sufficiently great consensus elsewhere may be good reason to doubt a belief, since “nothing pleases the many unless it strikes the imagination, or binds the understanding with the bands of common notions” [B1A77]. The opportunity to challenge something which may otherwise go unchallenged should not be lightly discarded.

If the multitude assent and applaud, men ought immediately to examine themselves as to what blunder or fault they may have committed.

B1A77, Novum Organum

Invoking logic ⚖️

Deduction alone is insufficient grounds for belief.

Syllogisms rely on assumptions and inferences to justify their conclusions. These need to come from observation and interpretation, or else from necessity (for example, the assumption that truth is possible – though this may also be evidenced by the effectiveness of science).

Logical invention does not discover principles and chief axioms, of which arts are composed, but only such things as appear to be consistent with them. For if you grow more curious and importunate and busy, and question her of probations and invention of principles or primary axioms, her answer is well known; she refers you to the faith you are bound to give to the principles of each separate art.

B1A82, Novum Organum

These should be challenged and questioned, and what was once the best explanation should be challenged at the first sign of error in its predictions.

A model might be internally inconsistent, but that doesn’t mean it matches reality. Especially long deductive arguments requiring many assumptions or inferences are definitely to be avoided unless the intermediary conclusions are also backed up by observation.

Even once you come up with a model that matches what you’ve previously observed, you need to make new predictions with it in order to compare it to other reasonable explanations.

The syllogism consists of propositions, propositions consist of words, words are symbols of notions. Therefore if the notions themselves (which is the root of the matter) are confused and overhastily abstracted from the facts, there can be no firmness in the superstructure. Our only hope therefore lies in a true induction.

B1A14, Novum Organum

Relying on experience 📸

You can’t do science without experience, but uncontrolled anecdotes aren’t very good evidence.

As with consensus, any belief matching personal experience should be questioned.

Bacon compares a reliance on serendipitous observation or personal anecdote to “a mere groping, as of men in the dark, that feel all round them for the chance of finding their way, when they had much better wait for daylight, or light a candle, and then go” [B1A82].

The true method of experience … first lights the candle, and then by means of the candle shows the way; commencing as it does with experience duly ordered and digested, not bungling or erratic, and from it educing axioms, and from established axioms again new experiments; even as it was not without order and method that the divine word operated on the created mass.

B1A82, Novum Organum

We need a more systematic approach to designing experiments and measuring results.

Ignoring the Obvious ⚡️

The least interesting things are usually the easiest to ignore.

Bacon notes that “things of familiar and frequent occurrence … are received in passing without any inquiry into their causes” [B1A119].

A theory needs to explain the basics as well as the weird stuff.

Whatever deserves to exist deserves also to be known, for knowledge is the image of existence; and things mean and splendid exist alike.

B1A120, Novum Organum

In fact, if we want to avoid “flying to universals” [B1A64], we should probably start by explaining the simplest, most common examples of a phenomena.

Of course, we can’t stop there – the weird stuff does need explaining, but once we have theories that work in normal situations, we can use counterexamples to figure out which decent theory is the best.

Bacon’s method doesn’t aim to satisfy curiosity, it aims to find the truth.

Scientists need to introspect as well as observe – not because truth is within them, but because they need to see reality through a clear lens.

I am not raising a capitol or pyramid to the pride of man, but laying a foundation in the human understanding for a holy temple after the model of the world. That model therefore I follow.

B1A120, Novum Organum

4. Discovery is Possible

If they could bind themselves to two rules – the first, to lay aside received opinions and notions; and the second, to refrain the mind for a time from the highest generalisations, and those next to them – they would be able by the native and genuine force of the mind, without any other art, to fall into my form of interpretation. For interpretation is the true and natural work of the mind when freed from impediments.

B1A130, Novum Organum

Reasoning is hard, and sometimes we’re bad at it. But science is still great for predicting and explaining the behaviour of nature. Denying the possibility of truth doesn’t get us any closer to a good scientific method.

Truth is always going to be filtered through our messy, biased brains – but we should aim to eliminate the mess and the bias as much as we can. We can’t control the world if we don’t understand it.

By far the greatest obstacle to the progress of science and to the undertaking of new tasks and provinces therein is found in this – that men despair and think things impossible … if therefore anyone believes or promises more, they think this comes of an ungoverned and unripened mind, and that such attempts have prosperous beginnings, become difficult as they go on, and end in confusion.

B1A92, Novum Organum

Being equally skeptical about everything doesn’t suggest that we draw conclusions in a particular way. It doesn’t help us improve our scientific method, unless some alternative is suggested. In practice, “universal” skepticism is often applied only to claims which contradict personal beliefs.

Bacon’s skepticism elevates some scientific methods over others. It doesn’t deny the possibility of knowledge, but guides and corrects the way we obtain it.

It will also be thought that by forbidding men to pronounce and to set down principles as established until they have duly arrived through the intermediate steps at the highest generalities, I maintain a sort of suspension of the judgment, and bring it to what the Greeks call Acatalepsia – a denial of the capacity of the mind to comprehend truth.

But in reality that which I meditate and propound is not Acatalepsia , but Eucatalepsia; not denial of the capacity to understand, but provision for understanding truly. For I do not take away authority from the senses, but supply them with helps; I do not slight the understanding, but govern it.

And better surely it is that we should know all we need to know, and yet think our knowledge imperfect, than that we should think our knowledge perfect, and yet not know anything we need to know.

B1A126, Novum Organum

The Baconian Method 🥓

Now my method, though hard to practice, is easy to explain; and it is this. I propose to establish progressive stages of certainty. The evidence of the sense, helped and guarded by a certain process of correction, I retain. But the mental operation which follows the act of sense I for the most part reject; and instead of it I open and lay out a new and certain path for the mind to proceed in, starting directly from the simple sensuous perception.

Preface, Novum Organum

After pointing out all the reasons why good science is hard, Bacon gives a few examples of how to do it properly. He starts by exploring heat, making three different tables:

- Table of Essence and Presence [B2A11] – Bacon provides diverse examples of heat, such as sunlight, hot springs, and fire

- Table of Absence in Proximity [B2A12] – These are examples of the absence of heat, but each in correspondence with the entries in the first table; to sunlight he compares moonlight; to hot springs, cool bodies of water; to flame, glowworms and other illuminations. Bacon notes various experiments which may performed upon the different instances or absences of heat, with differing results.

- Table of Degrees [B2A13] – Bacon organises such examples into gradations, showing for each the different extents of heat that may be found within instances of the same substance, or across different substances.

Bacon wants to find the “true form” of heat.

Heat need not be material; sunlight is hot.

Heat need not require illumination; boiling water is hot.

Heat cannot arise from air alone, for air is often found cool.

We need to identify what is common to all things that are hot – not just most. This is the method of “rejection” and “exclusion” [B2A16].

Various reasonable assumptions about heat are rejected by observations. Various reasonable hypotheses are excluded if their predictions do not match reality.

This process of gradual elimination leaves no room to “jump and fly from particulars to axioms remote and of almost the highest generality” [B1A104].

Then, and then only, may we hope well of the sciences when in a just scale of ascent, and by successive steps not interrupted or broken, we rise from particulars to lesser axioms; and then to middle axioms, one above the other; and last of all to the most general.

B1A104, Novum Organum

🌶♨️

Why is it important to slow the progression from observations to theories?

We need to leave room to compare our conclusions to reality.

Simpler inferences make it easier to spot incorrect induction.

We might have false assumptions, a biased sample, bad judgement, or poor understanding – but comparing theories with data keeps us on track.

Whenever you “derive” general principles from only a handful of examples, you’re making assumptions.

Testing the principles can help reveal what these are, and whether they’re correct.

The more general the principle, the more assumptions there probably are.

This method gets rid of a lot of bad explanations which seem sensible before looking at the evidence.

It’s not perfect. It doesn’t tell you exactly how to come up with hypotheses to test. But it’s certainly better than blind intuition.

5. Learning Requires Progress

Bacon knew his method wasn’t perfect, and there’s still room for improvement after 400 years – “the art of discovery may advance as discoveries advance” [B1A130].

For example, accepting a paper for publication often requires a p-value below a given threshold – but p-values don’t actually tell you whether a theory is good. In fact, they’re another example of “naive induction” [B1A105]. In this sense, the submissions process still has room for improvement.

According to Bacon, three things get in the way of scientific progress: “reverence for antiquity … the authority of men accounted great in philosophy, and … general consent” [B1A84].

Modern thinkers have great advantages over ancient thinkers. Bacon notes that “the world in which the ancients lived … though in respect of us it was the elder … in respect of the world it was the younger” [B1A84]. The methods of Bacon and antiquity should be challenged by newer, better methods.

How do we figure out which methods work better than others?

First, we need to understand what the goal of science should be – it cannot be “composed for its own sake” [B1A98].

We need to evaluate different methods by their achievement of these goals.

This is, in large part, a sociological problem.

🏛🔍

Bacon looked around at the science of his day, and backwards to the history of discovery, and saw the potential for change.

If a man turn from the workshop to the library, and wonder at the immense variety of books he sees there, let him but examine and diligently inspect their matter and contents, and his wonder will assuredly be turned the other way.

B1A85, Novum Organum

Intellectuals were “ever saying and doing what has been said and done before” [B1A85].

Alchemists placed full faith in their methods, and “when the thing fails, lay the blame upon some error of their own” – but they still “made a good many discoveries and presented men with useful inventions” [B1A85], if only by accident.

The magicians directed their efforts “rather at admiration and novelty than at utility and fruit” [B1A85].

A new method of discovery was called for.

Seeing mixed results, Bacon was at once disappointed and optimistic.

He took from these systems the things that worked.

He expected progress in method to drive progress in discovery.

He was right.

Works Referenced

D. Abbott, 2016, Should You Trust Unanimous Decisions?, TED-Ed

R. J. Acton, 2017, An Intuitive Explanation of Inferential Distance, LessWrong

S. Alexander, 2020, Confirmation Bias As Misfire Of Normal Bayesian Reasoning, LessWrong

F. Bacon, 1620, Novum Organum

I. Douven, 2011, & E. N. Zalta, 2017, Abduction, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

S. J. Gould, 1997, Nonoverlapping Magisteria, Natural History 106, p.16-22

HistoryExtra, 2019, Have Nuclear Weapons Helped to Maintain Global Peace?

P. C. Hodgell, 1994, Seeker’s Mask

D. Main, 2019, Like Chess Players, These Crows Can Plan Several Steps Ahead, National Geographic

National Science Foundation, 1953, What Is Basic Research?, Annual Report §6

S. Parrish, 2016, Francis Bacon and the Four Idols of the Mind, Farnam Street

G. Rees & M. Wakely, 2004, The Instauratio Magna, Part II: Novum organum and Associated Texts, Oxford: Clarendon

G. Rey, 2003, & E. N. Zalta, 2020, The Analytic/Synthetic Distinction, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The School of Thought, YourLogicalFallacyIs.com

N. Thomas, 2009, & E. Zalta, 2017, Scientific Revolutions, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

E. Weiner, 2016, What Made Ancient Athens a City of Genius?, The Atlantic

E. Yudkowsky, 2007, Making Beliefs Pay Rent (in Anticipated Experiences), LessWrong

Discover more from quantia

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.